Do you have forward head posture, or do you have a friend or family member who does? Perhaps you’re always telling them to stand up straight, but they just can’t seem to do it. Let’s talk about the neurology and physiology behind forward head posture and most importantly, what you can do about it.

Rather watch or listen than read?

Three things that contribute to forward head posture:

- Decreased tone in the trapezius muscle and increased tone in the sternocleidomastoid muscle

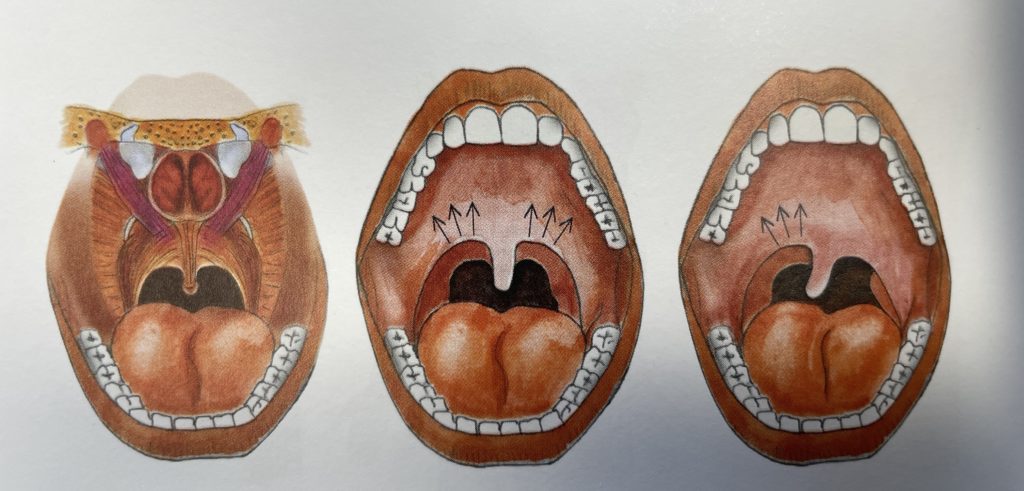

This is typically due to some kind of breathing dysfunction. That can be from an airway issue such as nasal valve collapse, deviated septum, chronic allergies, jaw issues, enlarged tonsils, just to name a few, which contributes to poor breathing mechanics, breathing more from the neck and shoulders as opposed to the abdomen and diaphragm. It can also be caused by a stressful event, trauma, or even chronic ongoing stress. This specific imbalance in these muscles is what contributes to forward head posture. Additionally, people that have asthma or COPD will almost always have a forward head posture.

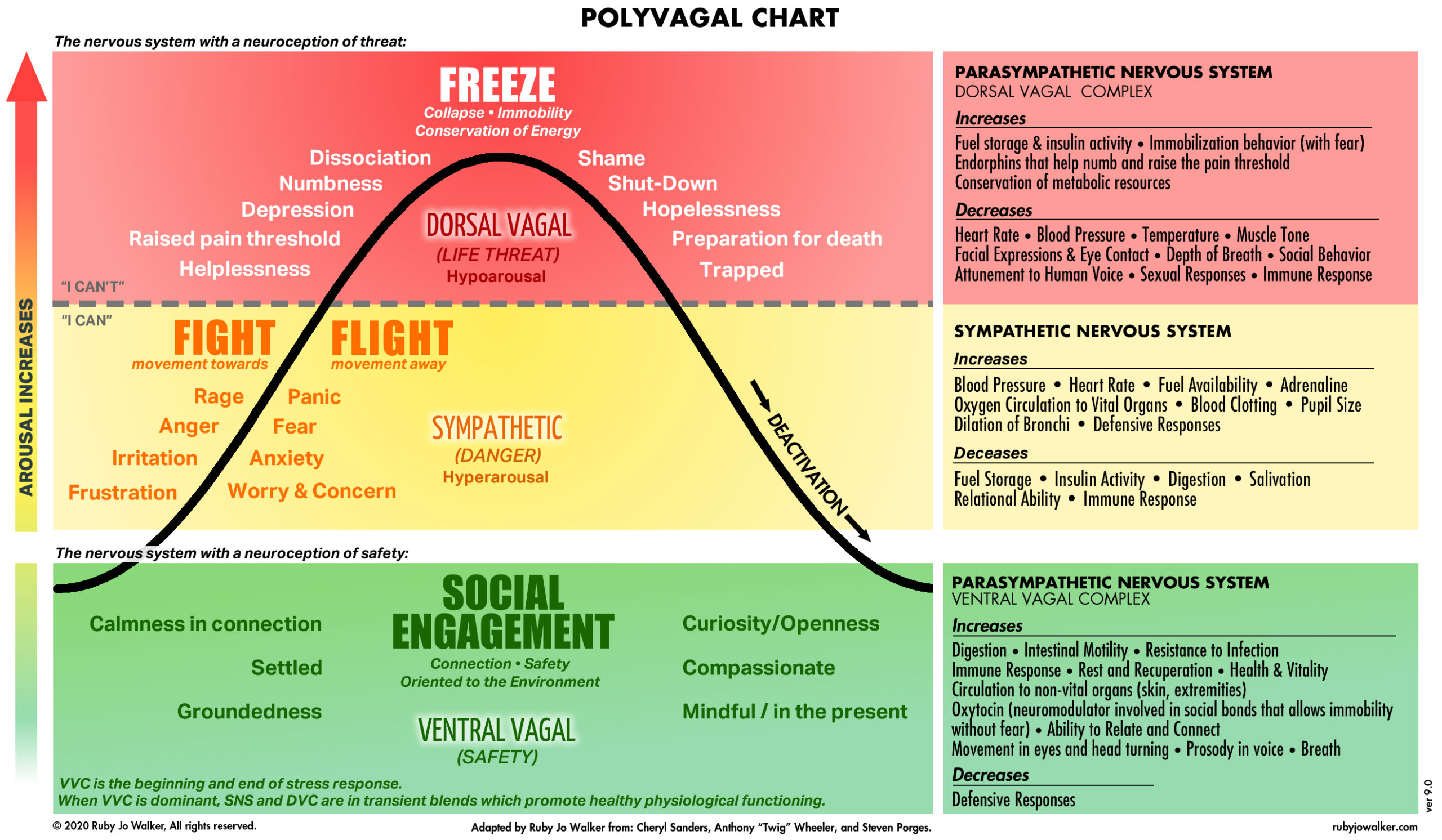

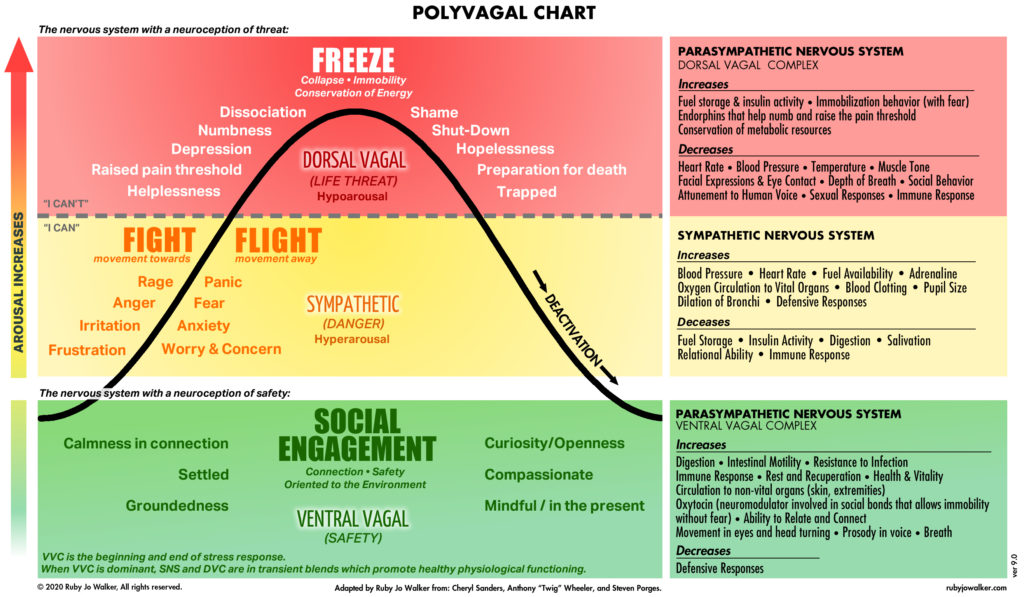

2) State of the nervous system

If you are in a chronically stressed state, perhaps a fight or flight state, or even a freeze state where you feel shut down, how you hold your posture will be impacted. Your posture is your story and how you present yourself to the world. Do you walk into a room with confidence and standing up tall, or do you feel shy, reserved, and rounded forward? All of your thoughts, emotions, beliefs, and activities impact your posture. We can’t simply think about your forward head posture as a plumb line. It is so much more than that.

3) Scars

No matter where the scar is or how old it is, it can affect your breathing, emotions, and movement. Scars contribute to postural changes, shifts in the nervous system, and contribute to muscle imbalances. It’s important to look at any scar in your body no matter where it is or what it’s from, and begin to address the scar from a fascial perspective. This means that doing scar work can influence your emotions, breathing, and movement.

Now that you have three causes, let’s talk about three solutions. So, when we’re thinking about how we’re going to shift this forward head posture, we have to think beyond just simple exercises such as chin retractions and thoracic mobility. We have to think about the cranial nerves because they are impacting our nervous system, facial expression, and whether we’re in a state of social engagement, which means we’re mindful, joyful, and grounded. We’re going to address this more so from a cranial nerve perspective and optimizing breathing so that you can make a change immediately. You can also have a cumulative effect the more that you do these.

What I would recommend before you start the exercises is to have someone take a side view picture of your forward head posture. Then, take one again after you finish the exercises to see if there is a change. There absolutely should be at least a subtle change if not a very noticeable change.

Three solutions for forward head posture

Three solutions for forward head posture

1) The Basic Exercise

With this, you’re putting input to the back of your head and looking with your eyes to create more blood flow around the brainstem. This is where the vagus nerve originates. What happens when we’re not in a state of social engagement is our first two vertebrae can become slightly misaligned. By bringing blood flow to the area and stimulating the vagus nerve can bring the first two vertebrae back into alignment, which means we’re back into a state of social engagement. This can impact your forward head posture almost immediately.

To perform the basic exercise, interlace your fingers and bring them behind your head. Look with your eyes only in one direction until you sigh, swallow, or yawn. When you’ve done that, repeat on the other side. This should take approximately 30 to 60 seconds, however, it can take longer depending on if your nervous system is ready to relax

2) The Salamander Exercise

This is also a cranial nerve reprogramming exercise, which will help to create more space in the chest cavity, the heart, and the lungs, therefore impacting breathing and forward head posture.

To perform the salamander, assume a table position. Look with your eyes first and then your head as you bring your ear to your shoulder and hold that for 30 to 60 seconds. Repeat on the other side again making sure you lead with your eyes, then side bend your head bringing your ear towards your shoulder.

3) The Trapezius Twist

This is essentially waking up all of the trapezius muscles. It’s not stretching or strengthening them. It’s just waking them up, which means there will be an immediate change in posture, breathing, forward head posture, as well as overall posture. Especially after you’ve been sitting for some time, get up and do these three twists! You won’t be disappointed.

To perform this exercise, start with your arms grasped together at waist level rocking back and forth. Next, move your arms up to the heart line rocking them back and forth. Lastly, raise your arms slightly above your shoulders and once again rock them back and forth. You should do about five to ten repetitions at each position.

There you have it, some causes for forward head posture and most importantly some solutions. We do have to remember that with forward head posture it becomes a vicious cycle because the more forward the head is the more blood flow that is constricted from the vertebral arteries. This means less blood flow to the brain. It also is affecting our airway which means it’s impacting our lymphatic system, hormonal system, and causing inflammation in the body. It’s really important to understand the neurology and physiology of forward head posture and begin to think about it from a much different perspective rather than simply corrective exercises like the chin tucks, upper back stretches, and retractions. We want to think of it especially from a nervous system perspective.

Reach out for a 15 minute FREE discovery session to see how we can help you on your journey.

For more content, make sure to subscribe to my YouTube channel here.

Other things that may interest you: