With anxiety, depression and stress on the climb, have you ever wondered how you can understand your reactions to life’s challenges and stressors? Or maybe you wondered how you can become more resilient? Did you know that you can map your own nervous system? This is such a powerful tool that can help you shift the state of your nervous system to help you feel more mindful, grounded, and joyful during the day, and more importantly during your life. Before we discuss how to map your nervous system, let’s break down the autonomic nervous system a bit more.

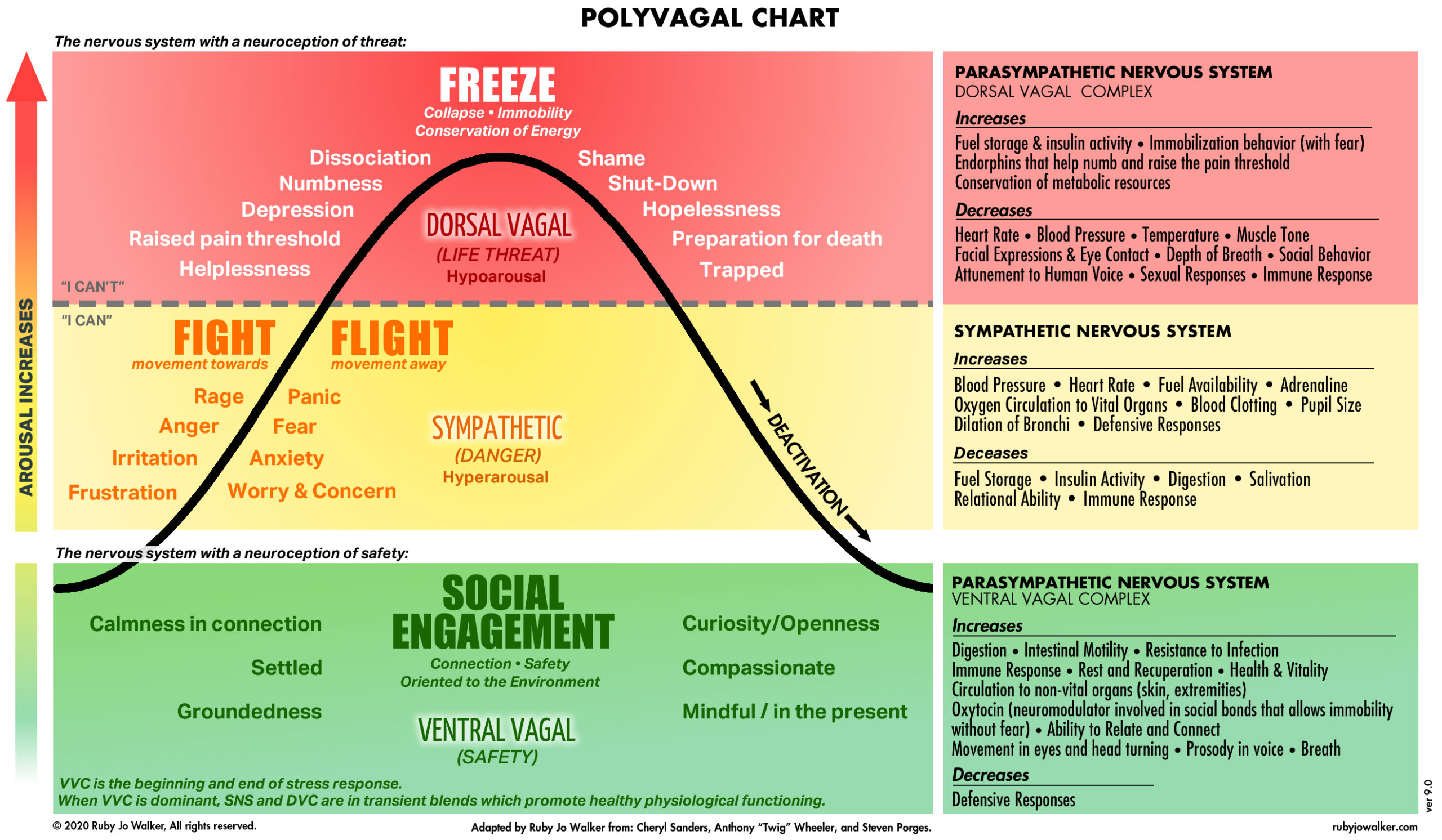

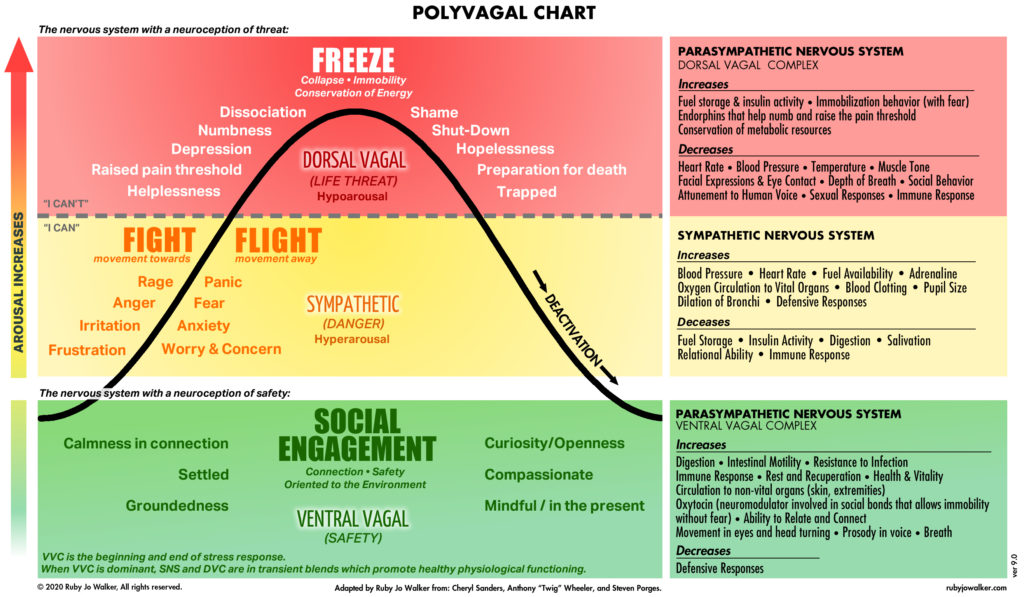

The terms “fight or flight” and “rest and digest” are typically what we refer to when discussing this autonomic nervous system. However, there are three different aspects of the autonomic nervous system referred to as the polyvagal theory, developed by Dr. Stephen Porges. The vagus nerve, referred to as the wandering nerve in Latin, is one of the longest nerves that originates in the brainstem and innervates the muscles of the throat, circulation, respiration, digestion and elimination. The vagus nerve is the major constituent of the parasympathetic nervous system and 80 percent of it’s nerve fibers are sensory, which means the feedback is critical for the body’s homeostasis. This amazing vagus nerve is constantly conveying information back to our brain. For example, when we take slow deep breaths, we are stimulating the vagus nerve. This will cause the release of a neurotransmitter called acetylcholine, which signals back to the brain to create this relaxation response. Pretty amazing, wouldn’t you say?

When we are in this stressed state or potentially anxious state, then we cannot be curious, or be empathetic at the same time. In addition to not being able to be empathetic or curious, we are also not able to bring the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain responsible for executive function, communicating, guiding, and coordinating the functions of the different parts of the brain, back online. This essentially means that we are not able to regulate our attention and focus. Sound familiar?

Three nervous system states

- First, our “fight and flight” response is our survival strategy, a response from the sympathetic nervous system. If you were going to run from tiger, for example, you want this response to save your life. When we have a fight response, we can have anger, rage, irritation, and frustration. If we are having a flight response, we can have anxiety, worry, fear, and panic. Physiologically, our blood pressure, heart rate, and adrenaline increase and it decreases digestion, pain threshold, and immune responses.

- Second, we have a “freeze” state, our dorsal vagal state, which is our most primitive pattern, and this is also referred to as our emergency state. This means that we are completely shut down, we can feel hopeless and feel like there’s no way out. We tend to feel depressed, conserve energy, dissociate, feel overwhelmed, and feel like we can’t move forward. Physiologically, our fuel storage and insulin activity increases and our pain thresholds increase.

- Lastly, our “social engagement” state is a response of the parasympathetic system, also known as a ventral vagal state. It is our state of safety and homeostasis. If we are in our ventral vagal state, we are grounded, mindful, joyful, curious, empathetic, and compassionate. This is the state of social engagement, where we are connected to ourselves and the world. Physiologically, digestion, resistance to infection, circulation, immune responses, and our ability to connect is improved.

Rather watch or listen than read?

As humans, we have and will continue to experience all of these states. We may be in a joyful, mindful state and then all of a sudden due to a trigger, be in a really frustrated, possibly angry state, worried about what may happen to then feeling completely shut down. This is human experience. We are going to naturally shift through the states.

However, when we stay in this fight or flight or this shut down/freeze state, that is when we begin to have significant physiological effects and also mental/emotional effects. As I mentioned earlier, this could be an emergency state. This can also be a suicidal state, if we are in this shut down mode for too long. If we are in a fight or flight state, we can have constant activation of our stress pathway, also known as the HPA axis, and we can really impact our stress hormones, sex hormones, our thyroid, etc. This stress will have significant inflammation effects on the body as well. All of these states can have considerable effect on our overall health, positive or negative, of course. Also, you can not get well if you are not in your “safe” state. No treatment intervention or professional will help you if you are not safe. This is why it’s really important to identify the states for each of you.

How can you map your nervous system? According to Deb Dana, there is a simple and effective approach in her book, the Polyvagal Theory in Therapy.

- Identify each state for you.

The first step is to think of one word that defines each one of these states for you. For example, if you are in your ventral vagal state, this is also called the rest and digest state, you could say that you feel happy, content, joyful. etc.

When you are in your fight or flight state you could use the words worried, stressed, overwhelmed, etc.

In the freeze state you could use the words shut down, numb, hopeless, etc.

The first step is identifying the word that you correlate with each of those three states. This is really important because then you’re able to recognize which state you are in and identify with it quickly. This will allow you to really tune into your body and understand how you feel in that state, so you can help yourself get out of it.

2. Identify your triggers and glimmers.

You’ll want to identify triggers for your fight/flight state as well as your freeze state. These could be things like a fight with your boss, an argument with your spouse, a death of a loved one, if someone cuts you off while driving, etc. It is whatever things that cause you to feel stressed. You want to eventually have at least one trigger, if not many, written down for each of those states.

Glimmers are the things that bring you to that optimal nervous system state. It could be something as simple as petting a dog or something bigger like going on a vacation.

For more on Deb Dana’s work and her Polyvagal resources visit: www.rhythmofregulation.com.

Summary

Once you can identify what those states are for you, then you can recognize what your triggers and glimmers are for that state. You can really begin to make a profound difference in your nervous system state. You can take ownership of what’s happening to your body, you can tune in to what’s happening, and know how to regulate your emotions and your responses to stress. Ultimately, this is how we can begin to develop resilience. This means being able to have respond appropriately to life’s challenges, go to that fight or flight state for a short period, and then return back to your state of social engagement. That should happen a few times a year not multiple times a day, or every day for that matter. To truly enjoy life, returning to your state of safety where you are mindful, grounded, and joyful, is a practice. It can start with mapping your own nervous system.

If you need help on your journey, please reach out!

For more content, make sure to subscribe to my YouTube channel here.

Other things that may interest you:

How to improve your vagal tone

References:

Dana, D., & Porges, S. W. (2018). The polyvagal theory in therapy: Engaging the rhythm of regulation. W.W. Norton & Company.

Porges, S. W., Porges, S. W., & Porges, S. W. (2011). The polyvagal theory: Neurophysiological foundations of emotions, attachment, communication, and self-regulation. First Edition ; the pocket guide to the polyvagal theory: The transformative power of feeling safe. first edition. W.W. Norton & Company.

ROSENBERG, S. T. A. N. L. E. Y. (2019). Accessing the healing power of the vagus nerve: Self-exercises for anxiety, depression, trauma, … and autism. READHOWYOUWANT COM LTD.